My Kraus

I was honored to write the program notes for Juilliard 415’s Feb. 9 concert with Kristian Bezuidenhout. While researching Joseph Martin Kraus’s overture to Olympie, I read the composer’s letters in translation, which, for reasons explained in this essay, moved me personally. Before reading, it is recommended that you peruse my notes on Kraus.

“For I have often thought of you — thought only of you – and for you I forgot father and mother who whine about me as a refugee. Your Kraus”

This letter, from the 22-year-old Joseph Martin Kraus to his friend Johann Friedrich Hahn, survives as a fragment.

Its translation is included in Bertil H. van Boer’s The Musical Life of Joseph Martin Kraus, published in 2014 by Indiana University Press.

It “remains a torso,” writes van Boer, “lacking an indeterminate amount of beginning text and salutation.”

“The final paragraph,” he continues, “seemingly couched in intimate language, is really no more than friendly Schwämerei, effusiveness without much substance.”

The Musical Life, being the first-ever German-to-English translation of the “Swedish Mozart’s” correspondence, is a major contribution to scholarship, without which essays like this wouldn’t be possible.

However, van Boer makes his opinion clear, throughout The Musical Life, that any speculation about Kraus’s sexuality is misguided. So abundantly clear, in fact, that it raises a few eyebrows.

In a letter to his parents, dated April 3, 1778 — a year before the above — Kraus writes:

“I have found apart from you, my loved ones, a single individual that I wanted to be loved by you as much as I was loved — the sure sign of friendship, which is rare. It is the young Hahn of Zweibrücken — the only one that I have met who is like me through and through — completely to the core — that I have studied down to the last fiber and remained as he once was and lost nothing in the analysis.”

In the footnotes, van Boer calls Hahn a “bosom friend,” noting that the letter is “replete in the language of male bonding of the time.”

Of course, when it comes to historical figures, we cannot ask them how they’d self-identify. And, as van Boer alludes, ideas and language around queerness are culturally specific. Besides, sometimes a composer’s sexuality is completely irrelevant to their work.

However — in the case of Kraus, especially — I argue such discourse is important.

First, because it inspires the next generation of queer classical musicians. Why should a figure like Kraus be assumed heterosexual before proven to be otherwise?

And second, because, I’d argue, there’s something inherently “queer” about the “sturm and drang” (more on that later).

What do we know about Kraus? His letters, as well as his criticism, are full of personality. He is called “opinionated,” “sarcastic,” even “caustic” by van Boer. Dare I add, shady?

Kraus was a bon vivant. He loved “wine, women, and song.” Minus, perhaps, women. Substitute in dogs. And hunting.

Some of his letters, in fact, appear to have been written while inebriated. The historical equivalent of “drunk texts.”

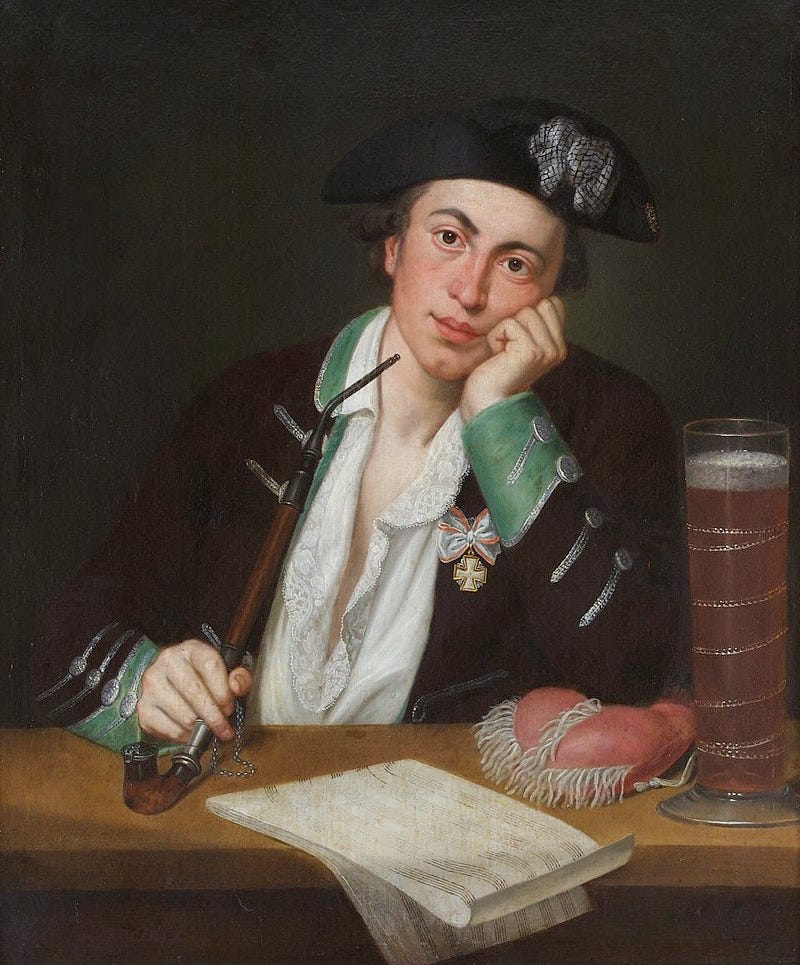

A portrait, attributed to Jacob Samuel Beck, of the 19-year-old shows Kraus with a long pipe and pint of beer, his hand resting on a flushed cheek.

Reading Kraus’s letters, I was struck by that “gut feeling,” that moment of recognition, which queer people are trained, by necessity, to look for in each other.

In a letter to Johann Samuel Liedemann, dated March 1785, Kraus writes:

“Those who love fire, love when it is stoked by bellows quite nicely; naturally — and thus so naturally that when I bound myself to my first friend Hahn, I bound myself forever… Fare well, my dear fellow, and may the assurance be a little comforting to you that Kraus has only one friend.”

In his introduction, van Boer writes of the “deliberate destruction” of some of Kraus’s letters by early biographers, including Fredrik Silverstolpe.

“The letters to Liedemann may have been considered too explicit in terms of their language, so that the possibility of a close, perhaps even intimate, relationship could have been construed,” writes van Boer.

Silverstolpe — who was close with Kraus’s surviving family — destroyed several other letters to Liedemann dated the subsequent July, August, November, and February.

“Silverstolpe censored what may have been considered normal for the male-bolding cult taking place during Kraus’s time,” writes van Boer, “but which in the following century could be seen as betraying unacceptable moral relationships.”

To me, this doesn’t make much sense, as Silverstolpe was only a decade younger than Kraus, and published the biography in 1809, hardly a brand-new epoch.

And while van Boer doesn’t give any equivalent examples from Kraus’s contemporaries, he does write, “Any conclusion that these could represent some sort of social impropriety is no more true than suggesting Mozart’s often explicit letters to his cousin represent an erotic, perhaps even indecent, attachment,” essentially comparing homosexuality and incest.

According to van Boer, letters “had to pass through several layers of inspection, from censors to ordinary people who were entrusted to transport or deliver them,” which required reading “between the lines.”

Yet van Boer doesn’t always read “between the lines” himself: “Given that he was a child of the linguistic peculiarities of the wildly emotional Sturm und Drang,” he writes, “it would be a mistake to read too much of a relationship or sexual orientation into them.”

There are no surviving letters from Kraus to female love interests, nor much evidence that this lifelong bachelor ever had any. However, in a letter to his parents, dated June 26, 1784, Kraus does write:

“Damned! Yesterday I became twenty-eight years old and still don’t have a wife!”

In a letter, dated July 31, 1784, responding to parental concerns that he might be spending too much time on “girls, wine, and other such things,” Kraus writes:

“Concerning the first… this year it has rather had little effect upon me. Why? That is a true secret — for only I and dear God know about it. To express myself more clearly, I would rather admit quite openly now that I have a much stronger antidote against such temptations than my dear mother gives me credit for. In short – for an entire year I have burned from head to toe, or rather unpoetically to say: I love the girl that I believe to have been created for me and for me, any glance into the eyes of another would be a mortal sin… A warm, real, fresh love in the breast of a lad perseveres in the face of all sorts of temptations better than all of the amulets on God’s green earth.”

Could Kraus be speaking of his “only one friend” Liedemann, changing pronouns for stealth’s sake?

In Kraus’s final letter to Liedemann, addressed “Dearly Beloved,” he writes:

“Now to your novel. My dear fellow! If only I could at this moment clasp you to me and embrace and kiss you completely for all of the pleasure that you’ve given me with it!”

The salutation, originally “Lieber Liebender,” van Boer writes, is “an unusual salutation under any circumstances.” Kraus sandwiches critique of Liedemann’s novel with more praise, ending with:

“Just another small word: I love you without reservation, my dear fellow. Do heaven ordain that we sometime wander calmly hand in hand into another better world!”

Liedemann, apparently, didn’t respond well to Kraus’s “tough love,” as the two had a falling out shortly thereafter.

In “Let’s Talk about Emotion,” a 2022 editorial for Eighteenth-Century Music, the musicologist Michael Spitzer makes the case for “emotion theory” as it applies to Kraus’s music. Specifically, the adagio from his piano sonata in E major.

“Through much of the eighteenth century, emotions were performed in private letters,” writes Spitzer, just as, “We may not know how we feel until we say the words ‘I love you.’”

While, “The nature of his relationship with Liedemann is impossible to know,” writes Spitzer, “Kraus’s language in this [final] letter is passionate bordering on the erotic.”

In the piano sonata, Spitzer writes, “the love affair is conducted between the listener and the music,” the affect oscillating between “solemn spirituality” and the German “Laune.”

Spitzer points out that the piano sonata and letter to Liedemann have similar “emotional cocktails,” that is, affection “spiked with harsh critique.”

“Was the Adagio from Kraus’s piano sonata, written in Stockholm in 1788, his final letter to Liedemann, ‘an die ferne Geliebte’, as it were?” asks Spitzer. While it can’t be proven, “We might feel, intuitively, that these claims ought to be true.”

“We might, at the very least, have a conversation about it,” he writes. “Because the discourse of emotion must, at last, be let out into the open.”

So, I believe, should the discourse on Kraus’s sexuality (something that Spitzer implies but doesn’t say outright).

What would it mean for this major proponent of what we now call the “sturm und drang” in music — itself associated with contrasts, contradictions, passion, and drama — to have been queer?

For queer musicologists like myself, quite a lot. Like Kraus, I hope that, one day, we may “wander calmly hand in hand into another better world!”