“Leave me alone!” the title says. But Man Ray’s Emak Bakia seems to invite touch.

I first came across the sculpture on the Museum of Modern Art’s website. At the time, I was working on “F-Hole,” an essay about getting a tattoo based on Le Violon D’Ingres. (The essay is part of my in-progress collection titled Organologies.)

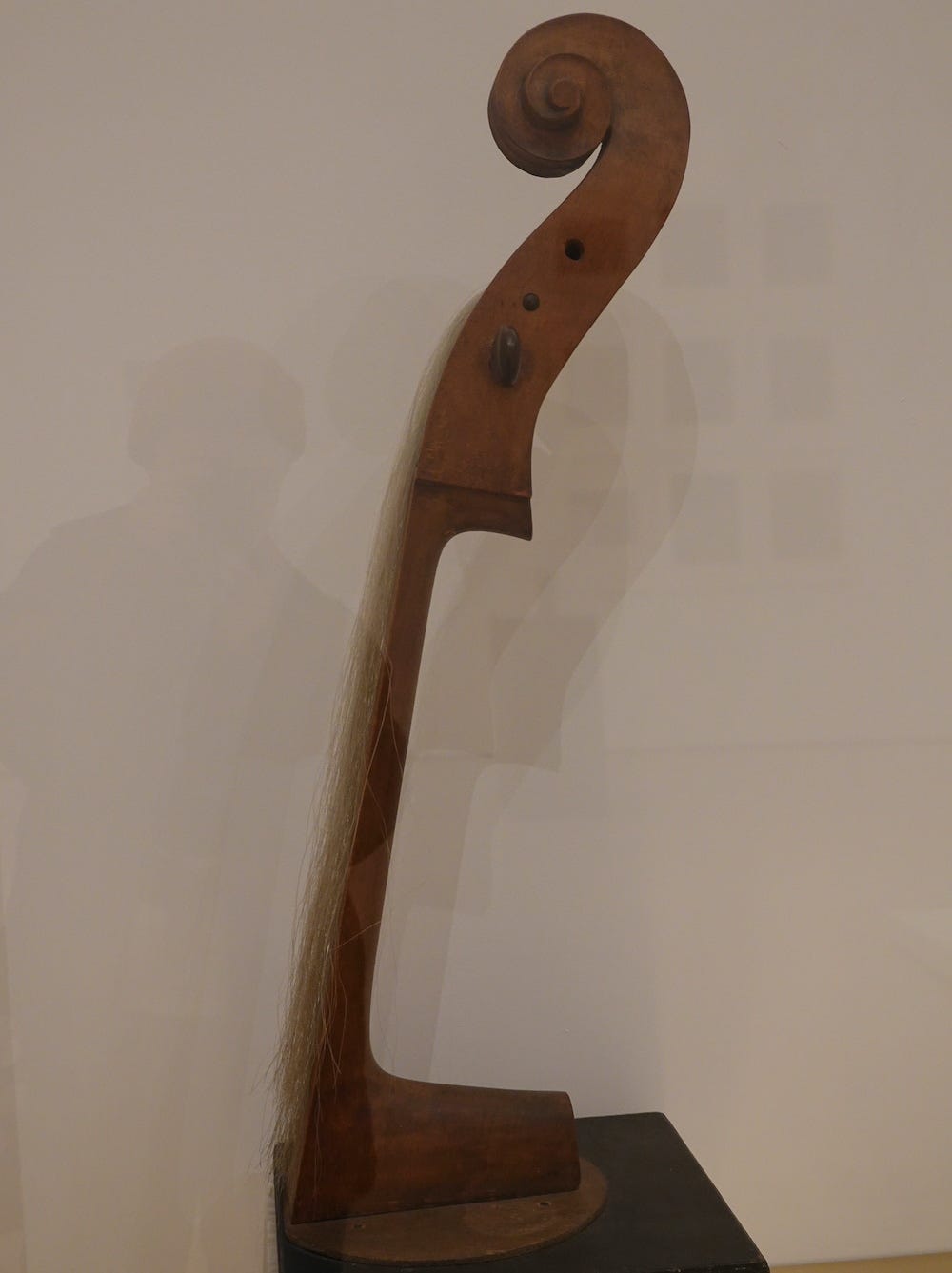

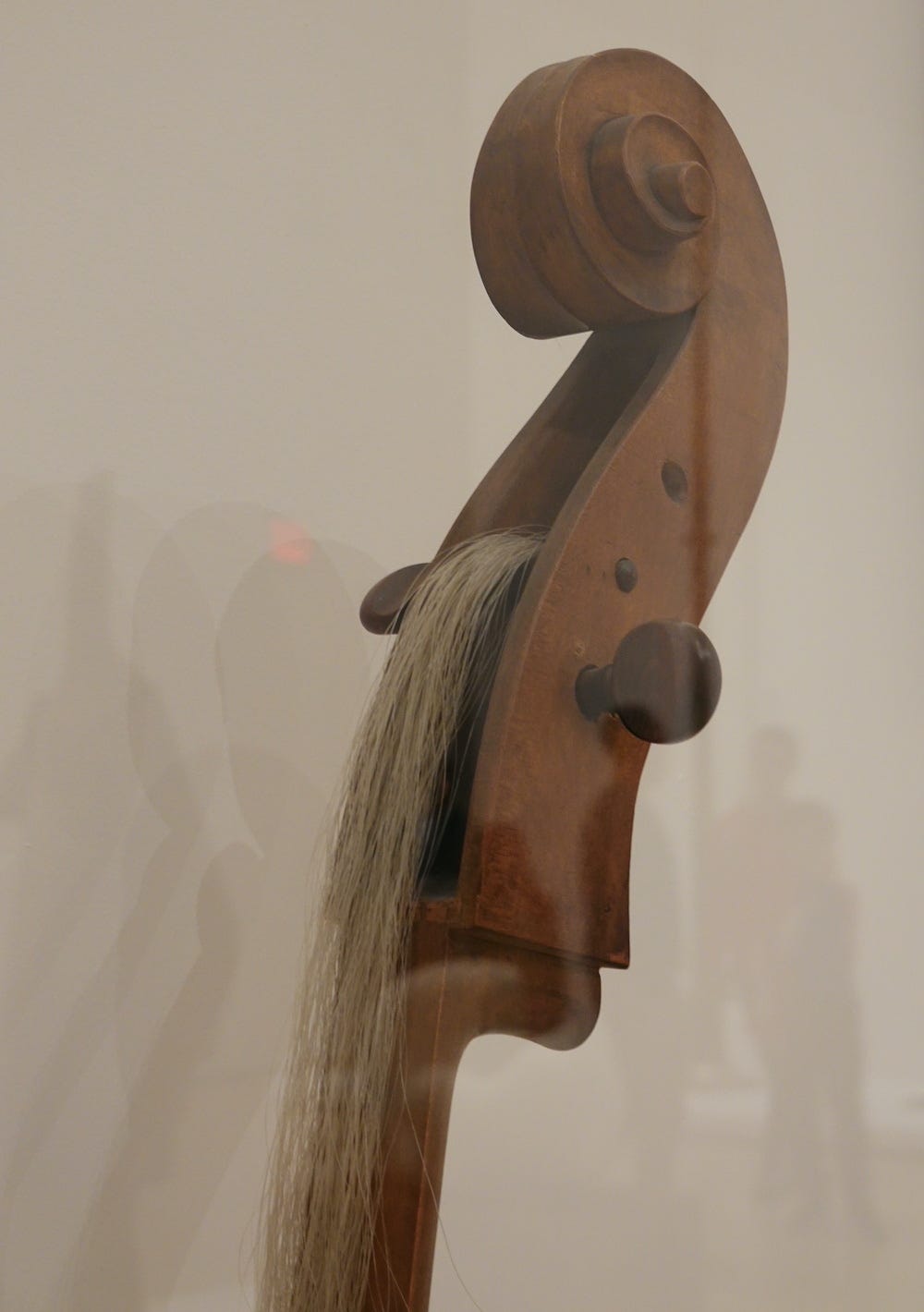

MoMA’s website says that Emak Bakia’s “amputated” instrument neck, which Man Ray found at a flea market, has flowing horsehair in the place of strings. The hair, which almost resembles a wig, “feminizes the instrument's curvaceous forms,” says the website, “and is the material typically used to make its bow.”

MoMA’s website describes it as an “instrument of frustration, from which no music will ever flow.”

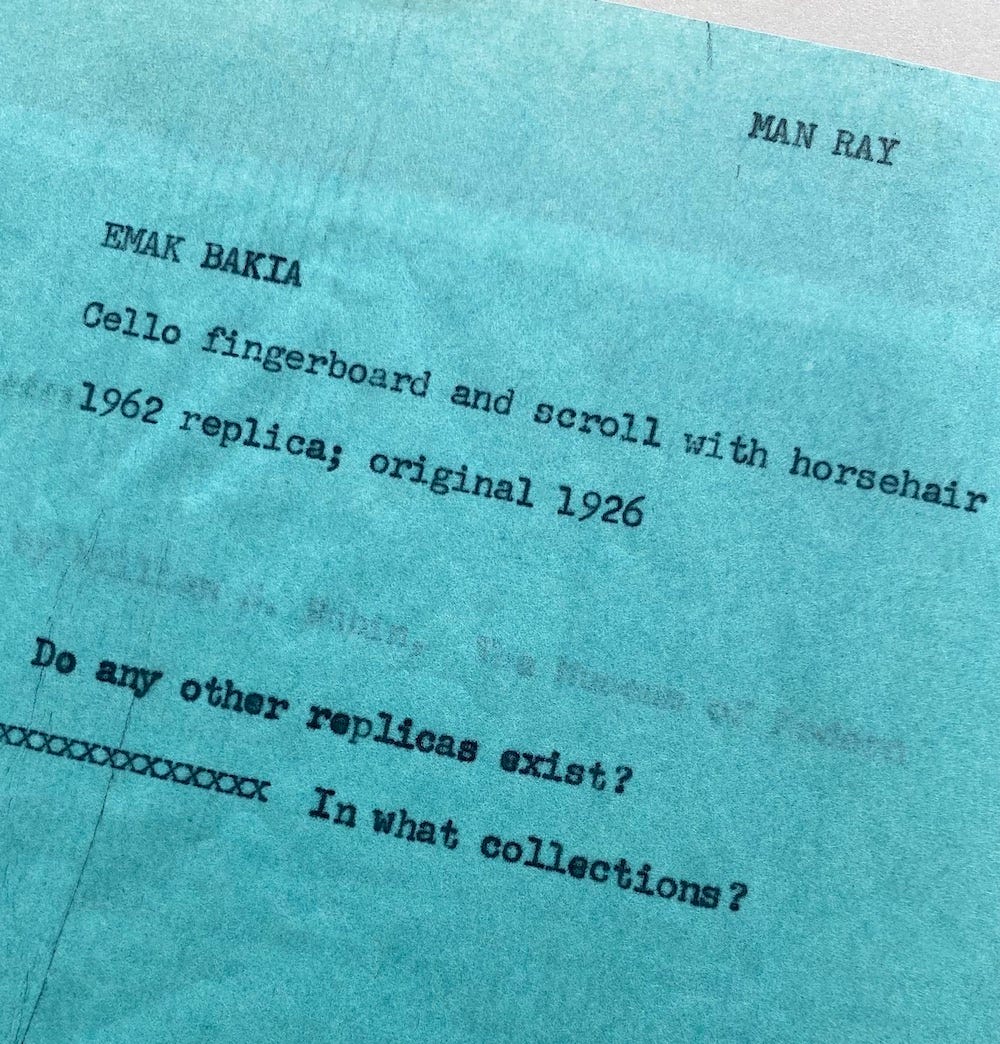

I notice a discrepancy, though: Among the materials are “cello fingerboard and scroll,” whereas the description calls it a “double bass.” I can’t tell which is correct from the photograph alone, though the number of peg holes — three — strikes me as suspect.

As Emak Bakia isn’t on display, I make an appointment at MoMA’s study center, to probe it with gloved hands. I receive an email response: “Most of our collection is stored offsite and viewing availability is not guaranteed due to staffing limitations.”

The best I can do, it seems, is look at Emak Bakia’s related materials.

After several run-ins with security guards, who insist I’m in the wrong place (I’m not), I finally make it into the building.

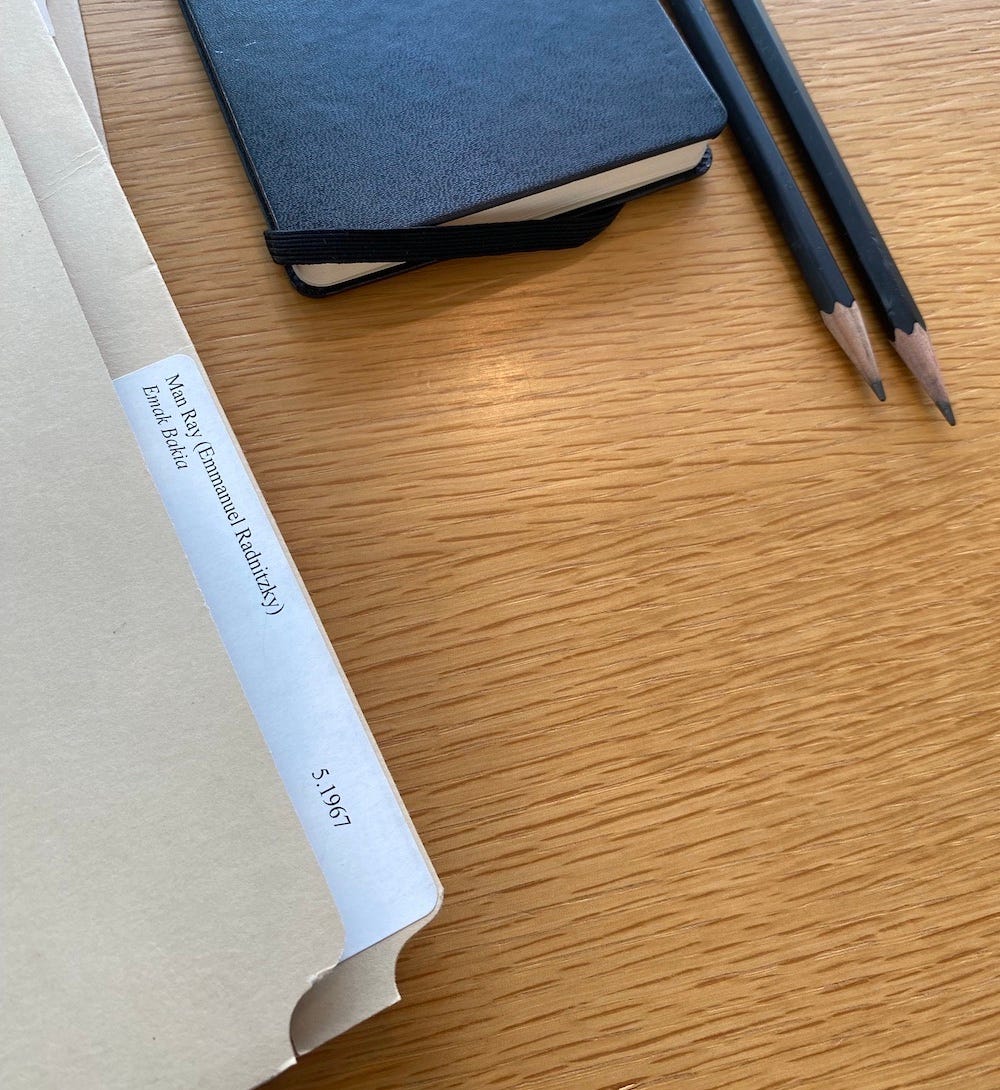

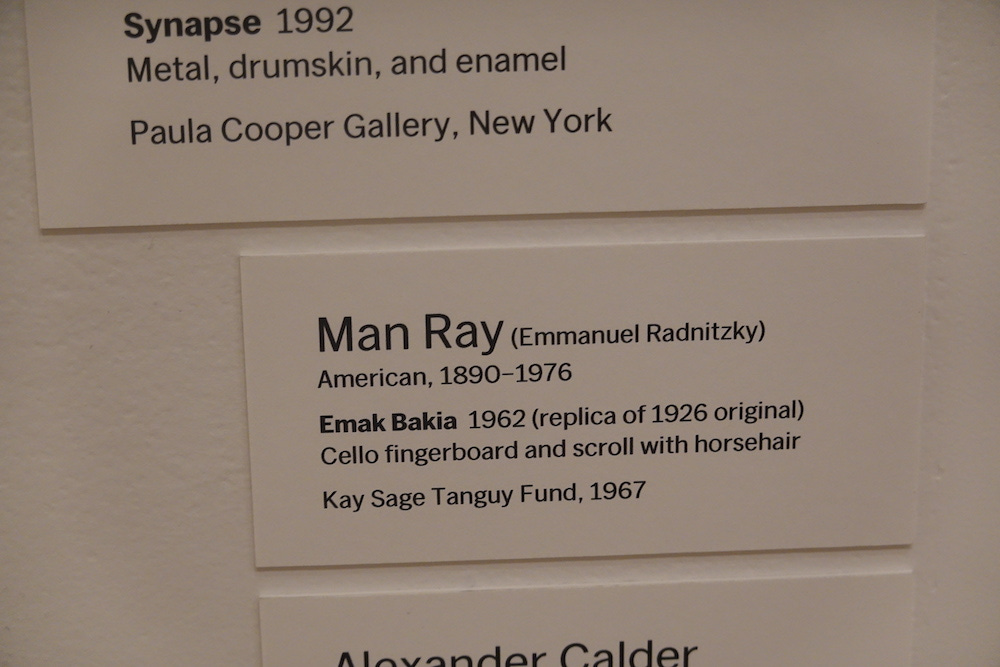

At the study center, which overlooks 5th Avenue, I parse through two manilla folders labeled “Emmanuel Radnitzky.” They contain photographs and accession records, including one that says:

It appears that the original Emak Bakia dates from 1926, the same year as Man Ray’s silent film by the same title. The Basque expression was also the name for Arthur Wheeler’s summer house, where Emak Bakia was shot.

The sculpture’s pegless prototype can be seen halfway through the film, which stars Wheeler’s wife, Rose.

This original Emak Bakia appears to have been lost. (Though I wonder about this “lamp” from 1934.) From it, several replicas were made:

MoMA’s, dating from 1962, which measures 742 x 145 x 271 mm, and has three peg holes.

The Tate’s, dating from 1970, which measures 510 x 197 x 260 mm, and has two peg holes.

And ten silver copies, also dating from 1970, with four pegs each, made by Studio Marconi in Milan.

Judging from the measurements, MoMA’s replica is much bigger than the Tate’s, suggesting the neck may have, indeed, come from a bass.

However, I’d have to see it in-person to be sure.

Just a few weeks earlier, I’d seen “Man Ray: Other Objects” at Gallery Luxembourg.

The show, which runs through Dec. 2, includes one of the largest collections of Indestructable Object, sometimes referred to as Object to be Destroyed.

They are all replicas — the original “possibly never existed,” says the exhibit catalogue.

Whether destructible or not, Man Ray’s Object is designed to be reproduced. Anyone can make one with a metronome, an eye, and a paperclip. (Mine drives the cat crazy).

Supposedly, a metronome regulated the Man Ray’s brushstrokes. The eye stands, in different accounts, for an imaginary audience to Man Ray's art-making, or a love interest, either Kiki de Montparnasse or Lee Miller.

Below a 1932 drawing of Object, May Ray writes, “With a hammer well-aimed, try to destroy the whole with a single blow.” This instruction perpetuates a kind of violence towards women’s “bodies.”

But even more interesting, I think, are the questions it raises about the locus of the “artwork.” Where is music located? Is it in the score, the instrument, the performance, the body? If we destroy one, what happens?

Similarly, where is identity located? Is it in the body or somewhere else?

After repeatedly prodding MoMA’s study center manager, I find out that Emak Bakia will soon be on display as part of “Spirit Movers,” an “artist’s choice” show curated by fashion designer Grace Wales Bonner.

On opening day — Saturday, Nov. 16 — getting into the museum was like going through airport security. Long strings of people being threaded through two metal detectors.

“Spirit Movers,” which runs through April 7, is in the free part of the museum — no tickets needed.

The exhibit banner shows Benjamin Patterson performing his Variations for Double-Bass. Within eyesight is Emak Bakia. It is in a display with an Alexander Calder ring and Bill Traylor watercolor.

Though the label says “cello,” it is immediately clear to me, from the proportions, that Emak Bakia is, instead, bass-derived.

Snapping photos of it — my own head, as well as those of other museum-goers, reflected in the glass — I notice a security guard eyeing me suspiciously. Also in the exhibit is Terry Adkins Last Trumpet, with the firm warning: “Do Not Touch.”

The exhibit is about sight and sound, of course, but also Black diaspora. And so, in this exhibit, Emak Bakia is an outlier, as Man Ray was certainly not Black. (Though he did once pose Kiki beside an African sculpture, to very questionable taste).

Indeed, I notice, in MoMA’s gift shop, that Emak Bakia is not included in Dream in the Rhythm, the exhibit’s catalogue.

Later that day, I reach out to that same MoMA manager, to let her know that Emak Bakia is mislabeled. “I will consult a colleague,” she says, “and get back to you with our internal decision regarding the medium line.”

The 3 peg holes is mysterious ..

Definitely a bass it seems to me …